Since it was introduced 23 years ago, the national minimum wage has raised the incomes of millions of Britons and reduced inequality.

Everyone loves it. For Labour politicians it’s a tool to reduce inequality, while for Conservatives it’s a way to force businesses to take on some of the burden of the welfare system. Technocrats get a sound policy based on impartial evidence, some of it provided by labour economists like me.

But, like that third ice cream, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. We can only push the minimum wage so far to tackle rising living costs such as spiralling energy bills before we need to use other labour market policies to address issues such as productivity.

With the UK facing a major cost of living crisis, the Trades Union Congress (TUC), which represents most unions in England and Wales, has called for a £15 an hour national minimum wage.

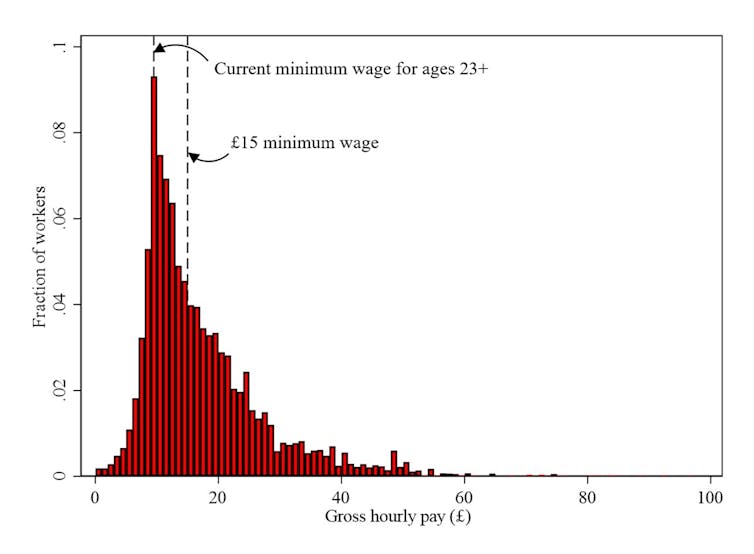

Economists gauge the level of the minimum wage by comparing it to the median wage, that is, the hourly wage of the person in the middle of a line-up of the best to least well paid people in the country. At present, British workers aged 23 years or more must earn a minimum of £9.50 each hour, which is equal to just over two-thirds of the median wage. In contrast, a £15 minimum wage would be equal to more than 100% of the UK median wage. In other words, more than half of British workers would be paid it.

Hourly pay of UK workers

Researchers have found that the minimum wage also affects the earnings of workers who earn slightly more than the minimum wage. This is because managers try to preserve wage gaps between pay grades, for example, by raising what supervisors earn when the minimum wage lifts the pay of check-out operators. That means the minimum wage indirectly affects even more workers.

A common concern about a minimum wage is that, if pushed high enough, it will eventually lead to unemployment. This is because firms are forced to pay their workers more than they would otherwise and may find no alternative but to lay them off to remain in business. There is no consensus around what this tipping point is, but the UK already exceeds 60% of the median and New Zealand’s minimum wage is at almost 80%, with no evidence of job loss as a result.

This means the TUC’s proposal could potentially be adopted without causing serious job loss. There are two major caveats to this, however, which illustrate the shortcomings of using the minimum wage as a tool to combat the rising cost of living.

First, a big part of the success of the national minimum wage in the UK has been the cautious and predictable way it has been rolled out over the past two decades. The government’s Low Pay Commission, which sets the amount, takes into account the economic conditions facing firms each year. This is why the minimum wage went up by just 1% in 2009, during the Great Recession, but by 7% in 2016, when the economy was more buoyant.

The TUC’s £15 proposal would represent a 58% increase. To avoid any risk of job loss, this would need to be phased in over several years, providing certainty for firms and a manageable increase in costs each year. But such a softly-softly approach would blunt the effectiveness of the minimum wage as a way to address the rampant inflation we are seeing right now. And unlike direct payments to households, it would do nothing to help those who don’t work or are self-employed.

Second, there’s no such thing as a free lunch: if unemployment doesn’t change in response to the minimum wage, something else will. Companies can accommodate the minimum wage by adjusting what I call the four “P”s: prices, profits, productivity or perks. Firms might cut back on perks such as overtime pay, bonuses or indeed free lunches to offset higher hourly wage costs, for example. But in my work I have found little evidence that this happens.

Firms do appear to eke out productivity gains from their workers by increasing the number of tasks they must do or reducing breaks, however. Most worryingly, managers seem to cut back on the amount of training workers receive in favour of squeezing more productive time from them. This may lead to lower wages later in those workers’ careers. In a study of British apprentices, I found evidence that, when employers were forced to pay a higher minimum wage after one year of employment, they responded by cutting the hours devoted to training.

One of the main ways many companies appear to accommodate the minimum wage is by passing on the costs to customers in the form of higher prices. Studies have found that some restaurants can recoup 100% of the costs of the minimum wage in this way. Of course this will contribute to the very problem for which the TUC wants to deploy the minimum wage, namely inflation.

On the other hand, the costs of the minimum wage often translate into lower profits. One study found that the unexpected announcement of a big increase in the minimum wage in 2015 led to a fall in the market value of the types of firms likely to be most affected, such as pub chains. However, there is probably a limit to how long company owners will accept lower profits before they adopt labour saving technologies or shut down business completely.

Addressing UK productivity

Beyond these considerations, a world in which more than half of the workforce has its wages set directly or indirectly by government would lack the wage “signals” that channel school leavers into booming occupations and provide employers with a rough guide of how productive a group of workers is.

The uncomfortable fact is that wages have not been growing in the UK because British workers have not been getting any more productive. That’s not because they lack “graft”, as some politicians seem to think, but due to a complicated mess of past policy failures affecting vocational training and third level education, and a lack of investment by firms.

A £15 minimum wage would mask, but not solve, these issues. Rather than using it as a panacea for all the ills facing British workers, we must tackle the trickier task of developing other effective labour market policies.![]()

Kerry L. Papps, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.